In his interview with The Paris Review, Roberto Calasso said the following:

I feel thought in general, and in particular what is unfortunately called “philosophy,” should lead a sort of clandestine life for a while, just to renew itself. By clandestine I mean concealed in stories, in anecdotes, in numerous forms that are not the form of the treatise. Then thought can biologically renew itself, as it were.

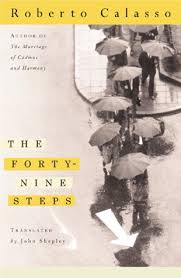

It would appear that Roberto Calasso’s own works set out to do just that. The 49 steps alluded to in the title of Calasso’s book refer to a sequence of meaning in the Talmud. Here, however, the sequence, or something like it, is used not on the Talmud but on the whole plane of western thought in the past few centuries.

In freeing himself from the philosophical treatise of which he spoke, abandoning the essay as we know it today with a strong supportable thesis, and without resorting to the constant chain of overcoming that often happens in western thought—you know, the easy academic distinction which believes that analytic philosophy supersedes Derrida, who supersedes Heidegger, who supersedes Nietzsche, who supersedes Plato—Calasso resorts to those very anecdotes, stories and other forms he favors to weave a narrative of the modern world.

The project that Calasso seems to take on here is a means of exploring those more latent features of history that, while not belonging to the socially accepted sequence of historical influence, may have left a definite imprint on modern consciousness.

One can’t so easily accuse him of jazzing around unseriously with history. Calasso, rather, seems to ascertain that if one doesn’t weave one’s own narrative, one is weaved by someone else’s narrative. Yet, all the while, he feels somewhat easy with the recognition that we are always wrapped up in some narrative not of our own making; another feature of life.

Most systems of thought have come about through someone trying to escape history, whether it be Marxism, The French Revolution or The Society of the Best Sunday Cheeses. Revolutions and intended revolutions, gigantic cultural gestures, act as instant points by which we can map out human progress or history.

Rather than escaping history, Calasso, rather, digs deep into the sediment of history, burrows through its tunnels, pays careful attention to its sequential blips and interruptions, comes out the other side and explores the secret rooms of the ancient cities of civilization. He walks the dark alleyways of society, lying adjacent to the boulevards filled with the humbuggy chants of party members making political changes, and in these alleyways a secret history is played out.

In Calasso’s narrative, everything new is actually an eventuation of something incredibly ancient. The peculiar, bisexually misogynistic message of Otto Weininger, which captivated a few college boys and girls in the early part of the twentieth century, is not a new psychological breakthrough but merely a more immediate and honest manifestation of how men have viewed women for countless millennia. Likewise, the mostly discarded writings of Marx (even by most Marxists) on the role of women in society can be seen as a hyper-reduction of an almost primitive tendency to view women as mere agents of sexual utility.

In like manner, many specific artists, politicians and historical figures make ‘cameos’—to use a theatrical phrase—on Calasso’s stage in order to embody a specific problem or a very distinct yet ongoing thread of thought or behavior. Yet, because this is not a story in the classic sense, Calasso’s narrative takes the form, not of a theatrical stage, but a sort of web. Each thread is connected to a different branch. Each essay is a branch on which Calasso sits for a time to gain a different thought.

He returns frequently to Walter Benjamin and Karl Kraus. There is one amusing anecdote in which Calasso tells us that we can ascertain the shape of Walter Benjamin’s thought by some of the things he reviews—as is the case when Benjamin employs his knowledge of Freud alongside philosophy of identity and pleasure when reviewing a book about toys.

Calasso’s frequent return to Kraus gives special attention to his prolific periodical, Die Fackel, along with The Last Days of Mankind. Kraus is depicted as the careful scribbler of uncareful half-truths and truth-and-a-halfs. Calasso gives us a picture of Kraus holed up during the Nazi-apocalypse, more intent on determining the perfect placement of commas than fighting the devil, with the firm belief that good grammar prevents future genocide.

Max Stirner earns an awkward place in the anxiety of influence, as most philosophers who’ve read him seem anxious to even admit his obvious influence on their work.

As Calasso weaves this narrative, it is easy to get lost in the euphoria of his poetic command. As a reader, I want to believe that his various curiosities and interests give us a more likely sequence of historical movement, even if it is only along some sub-current. But to trust the very finitude of Calasso’s narrative, bound by the walls of the book and its bindings, is to betray the spirit of the work, for part of the euphoria offered by the reading experience, I suspect, comes from a sense of inexhaustibility.

Following a similar trajectory through history as 49 Steps, there are all kinds of places one can go, suspicions one can entertain and conclusions one can draw. It acts almost as a mystery story through the walls of history, as we try to trace, not necessarily its origins, but how we relate to it.

Toward the book’s close, in a chapter called ‘The Terror of Fables,’ Calasso talks about our modern relationship with the word ‘myth’ and its having become a sneering synonym for ‘lie.’ He tries to restore myth as an ancient form of truth.

Thus now we can own up to what was—what is—that ancient terror that the fables continue to arouse. It is no different from the terror that is the first one of all: terror of the world; terror in the face of its mute, deceptive, overwhelming enigma; terror before this place of constant metamorphosis and epiphany, which above all includes our own minds, where we witness without letup the tumult of simulacra.

No, if myth is precisely a sequence of simulacra that help to recognize simulacra, it is naïve to pretend to interpret myth, when it is myth itself that is already interpreting us.

Perhaps it should be no wonder that Roberto Calasso only wrote one novel. After that, history itself was novel enough.